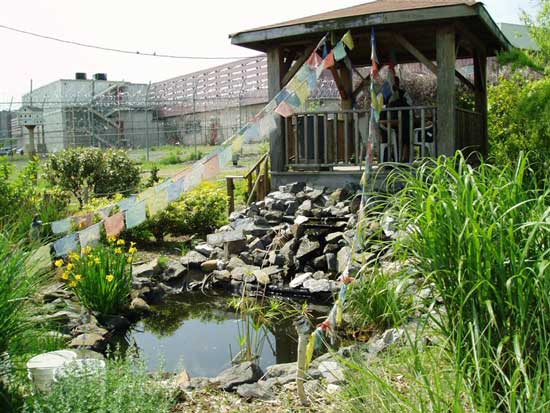

Photo by Michelle Parkins. "The response to the veterans survey about water really illustrated to me the connections veterans (and others) have with water as a healing aid."

I met Michelle Parkins last May when I was teaching at the Chicago Botanic Gardens Healthcare Garden Design Certificate Program, and was immediately impressed by her commitment to her MLA research project on gardens for veterans with PTSD and other combat-related issues. Since then, Michelle has completed her thesis, which is available as a beautifully bound book at www.lulu.com/product/paperback/soft-touch-for-a-silent-voice. Below is the thesis abstract and a bit about Michelle, a veteran herself.

Michelle (that’s her on the left in the red jacket), in collaboration with Annie Kirk, principal at Red Bird Design and founder of the Acer Institute, recently created Therapeutic Gardens for Veterans groups on Linked In and Facebook. These groups are a “Collaboratory to advance therapeutic garden environments as an extension of support and care for veterans & their families.” I encourage everyone interested in this subject to join in on the conversation.

Here is what Michelle writes about herself and her interest in this subject:

My adventures in life have seemed to always evolve around the military; growing up an ‘Army Brat’ triggered my interest. My time in the Navy consisted of great travel overseas and the education I received both in and out of Navy was invaluable. Due to an injury, my time in the Navy was cut short, however my respect for my fellow veterans and active duty military has never gone away. As a veteran using the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, I saw first hand the need and potential benefits for utilizing the outdoor garden spaces as VA hospitals and clinics. Although I have completed my Master’s of Landscape Architecture I plan to pursue the research and possible consultation of gardens for veterans.